Papaw’s Typewriter

Papaw’s study is perhaps the most vivid of my childhood memories. Everything about that room — the heavy oak desk, the southeastern window, every surface piled high with papers — has a mystical pull upon the deepest recesses of my mind that walking through Office Depot will frequently turn into a trip back in time.

A glimps in the corner of my eye of that display of neatly ordered packages of Ticonderoga No. 2’s conjures up the quiet Saturday ritual that was Papaw making notes for Sunday’s sermon — surely a masterpiece, which would never get delivered. Inevitably, somewhere between the house on Gerald Street and the church on Hadley, Papaw would turn to Mamaw and say, “The Lord’s spoke to me. I’m not preaching on the commandments.”

They had just been married a few months. She, his third wife, was a quick study. Instead of asking, “What did the Lord say,” she would instead just nod and await the revelation herself, when her husband would step behind the pulpit, grow two feet taller, and chastise whichever of the sinners in the congregation to which the Lord had instructed him to speak. Without notes, without any readily apparent signs of thought, Papaw would open the old Nelson King James Bible, so worn and familiar it would virtually fall open to the verse in question sheerly by the power of his will — or maybe His will. Papaw would remove from his pocket the No. 2 pencil, lay it on the pulpit beside his Bible, and begin to speak.

For many years, Papaw’s backside languished in an old dining room chair, the tissue-thin green cushion tied to the spindles providing the sole respite from the hard, worn oak. When that chair gave out and its bottom split wide, it was replaced for at least some period of time by a folding metal chair borrowed from the church fellowship hall, to which he affixed the same green cushion. One afternoon, he came home with an old office chair. Oak arms, an oak bottom, five coasters. And into the bottom of that chair went the green cushion. If that cushion went to the grave, tucked neatly under his rump in the coffin, I would not be surprised. (Surely someone must have thought to send it along with him!) I often wonder how he would have handled selecting a truly new chair from a store such as Office Depot, with row upon row of comfortable, cushiony heaven.

The paper department of any office supply store leaves its own wake of eddies through my childhood. Those yellow, spiral topped notepads and the erasable pens — surely the pinnacle of modern productivity technologies, ranked right up there with Corrasable Bond typing paper — lived scattered throughout the study. And look, there on the bottom shelf, forgotten and collecting dust, is a box of Wilson Jones ledger paper.

I’m not sure what, exactly, was the source of the aroma of his study. An alchemist’s brew of paper, dust, moisture and the rich, earthy musk of grease and oil. It may have been tracked in from the shop out back, where Papaw spent endless hours rebuilding hydraulic door closures. It may have been the grease he slathered onto the springs and wheels of that chair to prevent it from squeaking late at night. But I like to think it is another culprit, an almost silent, faithful companion of his ministry and my youth.

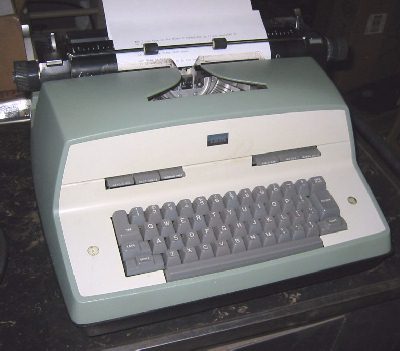

The IBM Model D Typewriter, similar to the one Papaw contended I demolished on several occasions. His was blue and white.

If I close my eyes, I can still hear it humming away from its perch on the homemade wooden table behind the desk. A machine of such immense value that the mere act of an eight-year-old pondering even looking at it was enough to warrant: the IBM Model D typewriter.

That a typewriter has a smell is something that may be surprising to those unfamiliar with the workings of this pre-wordprocessing workhorse of Corporate America. A look at the underbelly of the Model D will give you some idea of the workings. For beneath the twenty-plus pound monster’s sleek exterior lived — no, raged — an army of gears and pullies, levers and knobs, all of which performed vital tasks like moving the carriage a single space, engaging rocker arms to trigger the strike of a letter, and dinging the bell at the end of a line.

To keep all of these parts moving required regular maintenance in the form of a small, clicking can of oil that lived on the window sill above the table, beside the window unit air conditioner. A single drop of oil applied to the right spot would restore pep to a slow carriage return or repair that nagging double spacebar register every third or fourth word.

I sometimes wonder if that Model D is the reason I wanted so badly from such a young age to become a writer. Was inspiration something inate to that typewriter, to the sound of the roller taking in a crisp leaf of paper, of the key clicking and the almost inperceptible moment before the letter struck the page. And there was that hum.

Always, anytime Papaw was in the office, that hum was there. Steady, rhythmic, alive. And, always, anticipating.

This weekend, I started a quest to find Papaw’s old Model D typewriter. With any luck, it’s still somewhere in the extended family, languishing in a garage or a shed or the floor of a closet. Wish me luck. -md