Presidential Mettle Pt. 2: John F. Kennedy

(Author's Note) In honor of former President Trump, who has "endured more than any other president in the history of the United States of America," I thought we should share stories of other presidents who've endured challenges. Today's entry: President John F. Kennedy.

It’s easy to reduce John F. Kennedy’s role in history to his brief tenure as president and the assassin’s bullet that ended Camelot. But to do so would be a disservice to an individual who, even denied the presidency, left significant marks on history. In fact, Kennedy may well be one of the most consequential individuals of the 20th Century, presidency or not. But Kennedy’s path was far from simple, made difficult by chronic disease, frequent illness, and lingering effects from severe injuries suffered during his time in the service. Nevertheless, Kennedy overcame these obstacles–and a major rift with his father–to ascend the highest office and, in no small way, define the future of America.

Charting the inception of Kennedy’s rise to power proves difficult. Kennedy hailed from a prominent New England family. His father, Joseph P. Kennedy, was a prominent Boston businessman with deep connections in the community. The elder Kennedy had long held political aspirations, but numerous factors–least among which was his devout Catholicism–stoppered any hopes Joseph might have had to achieve elected office. Instead, Joseph Kennedy was relegated to a series of vital but appointed offices–chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, head of the U.S. Maritime Commission, and eventually Ambassador to the Court of St. James. As ambassador, Joseph Kennedy staunchly opposed U.S. entry in to the war against Adolph Hitler’s Germany. This opposition was rooted in his staunch isolationism and his belief that some form of appeasement might calm the waters of Europe and forego an escalation of conflict.

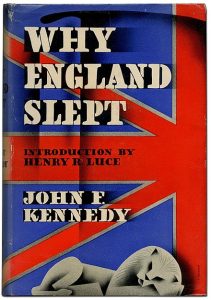

It is here, while Kennedy was at Harvard and his father in England, many historians begin to chart young John Kennedy’s rise. As is the case today, students in certain majors at Harvard were required to write and submit a senior thesis. However, Kennedy chose Government as his major, which lacked such a requirement. Students could, however, apply to write and submit a thesis. This is what he did, and it’s no small detail in the life and rise of John F. Kennedy. For his topic, Kennedy chose “the” issue of the day and wrote an extensive examination of the negotiation and drafting of the Munich Agreement. Under terms of this agreement, allied nations recognized the occupation and annexation of the German-speaking Sudetenland. This controversial decision had divided the world, and the Kennedy family would be no different. Kennedy’s thesis, “Appeasement in Munich,” drew conclusions that were distinctly anti-appeasement and, consequently, anti-Joseph P. Kennedy. As if a prominent member of a prominent family drawing sides against his father in an academic paper doesn’t seem like a big deal, consider this: Kennedy wouldn’t just write “Appeasement in Munich.” He would go on to expand the thesis into a full-length book, Why England Slept. The book was released in 1940 and proved wildly popular, landing particularly well with those supporters of President Franklin Roosevelt who were in favor of entering the war. Kennedy’s first foray into public life sold some 80,000 copies in the United Kingdom and the States and secured him roughly $40,000 in royalties–almost $900,000 by today’s money. It also opened up a deep rift between his politics and those of his father when Roosevelt cited the younger Kennedy’s arguments when firing Joseph P. Kennedy as ambassador in 1940.

It is here, while Kennedy was at Harvard and his father in England, many historians begin to chart young John Kennedy’s rise. As is the case today, students in certain majors at Harvard were required to write and submit a senior thesis. However, Kennedy chose Government as his major, which lacked such a requirement. Students could, however, apply to write and submit a thesis. This is what he did, and it’s no small detail in the life and rise of John F. Kennedy. For his topic, Kennedy chose “the” issue of the day and wrote an extensive examination of the negotiation and drafting of the Munich Agreement. Under terms of this agreement, allied nations recognized the occupation and annexation of the German-speaking Sudetenland. This controversial decision had divided the world, and the Kennedy family would be no different. Kennedy’s thesis, “Appeasement in Munich,” drew conclusions that were distinctly anti-appeasement and, consequently, anti-Joseph P. Kennedy. As if a prominent member of a prominent family drawing sides against his father in an academic paper doesn’t seem like a big deal, consider this: Kennedy wouldn’t just write “Appeasement in Munich.” He would go on to expand the thesis into a full-length book, Why England Slept. The book was released in 1940 and proved wildly popular, landing particularly well with those supporters of President Franklin Roosevelt who were in favor of entering the war. Kennedy’s first foray into public life sold some 80,000 copies in the United Kingdom and the States and secured him roughly $40,000 in royalties–almost $900,000 by today’s money. It also opened up a deep rift between his politics and those of his father when Roosevelt cited the younger Kennedy’s arguments when firing Joseph P. Kennedy as ambassador in 1940.

Strained relations between Kennedy and his father were just the first of several familial obstacles Kennedy would overcome during his career. After leaving Harvard, and with a best-seller to his credit, Kennedy aspired to attend Yale Law School. He was admitted to the starting class of 1941, but the looming specter of war changed those plans. Kennedy first sought admission to Officers’ Candidacy School, seeking a commission in the U.S. Navy. But he failed based on his life-long affliction with Addison’s Disease, a rare adrenal disorder in which the body underproduces cortisol. The condition can cause excruciating pain, which was the case for Kennedy. Throughout Harvard, over the course of his youth, the young and athletic Kennedy had been in constant pain. Addison’s didn’t deter Kennedy, whose determination to fight only grew in the face of this latest obstacle. Relying on a close family connection, Kennedy joined the Naval Reserves and was immediately activated and dispatched to the Office of Naval Intelligence as an ensign. He hoped to eventually serve on a PT boat–a small but nimble craft designed to hunt enemy vessels and sink them with torpedos. Kennedy’s father intervened on his behalf, providing the Department of Defense with false medical records and promising commanders of the fleet placing a young, handsome, bestselling author on patrol would bring positive publicity. (It did.)

With the help of his father, some faked documents, and a touch of fame, John F. Kennedy moved from ONI to the PT division. But the DOD weren’t morons. They had a high-profile asset to show off, and as they did with many such individuals, Kennedy was deployed to a “safe” post patrolling the Panama Canal. This didn’t sit well with the brash young leader, and he repeatedly petitioned for a more forward assignment. In 1943, shipped out to the Solomon Islands in the middle of the Pacific Theater. Here Kennedy assumed command of PT-109, the craft that would cement lasting fame and propel him along his path to the presidency. Kennedy had been in the Solomons more than three months when a bit of spotty intelligence suggested a Japanese naval onslaught was eminent. Orders came down dispatching fifteen PTs to repel a fleet of destroyers and other vessels. On the night of August 1, a Japanese destroyer rammed Kennedy’s PT-109 and ripped the vessel in half. Two crew members died instantly. For his part, Kennedy severely injured his back. However, Kennedy managed to wrangle his crew and swim more than three miles to an island.

He towed a badly burned crew member behind him, holding the strap of the man’s life vest in his teeth the whole way.

Kennedy’s leadership is credited with saving 11 members of his 13-member crew. His resourcefulness on the island also facilitated a rescue seven days later. As his father had promised, Kennedy proved a huge source of publicity for the Navy. The New Yorker ran John Hersey’s harrowing account of the PT-109 ordeal. (It’s worth the read, I assure you. It was also the basis for the 1963 hit motion picture PT-109.) Kennedy received a Purple Heart for his injuries and, somewhat strangely, he was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal–the highest non-combat award the Navy offers. This in spite of the fact that Kennedy’s heroism occurred in a forward combat role during an active enemy engagement. Both Kennedy and his father (and numerous other individuals) lobbied for the Navy to reconsider. Over the course of fifteen years following the war, Kennedy twice petitioned the Navy to reconsider his record for a Silver Star. His first petition resulted in a capitulation. If Kennedy agreed to return his Navy and Marine Corps Medal, he would be awarded a Bronze Star. The Navy repeated this offer in 1959, as Kennedy was preparing to run for President. Seeing the Bronze Star as a step down from the “highest non-combat award,” Kennedy declined the offer both times.

After the war, Kennedy lived with chronic pain from his severe back injury as well as the on-going effects of Addison’s. He underwent a series of painful surgeries, had multiple vertebra fused, and endured uncomfortable and sometimes questionable injections to help manage his pain. Nevertheless, Kennedy waged successful campaigns for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1947, the U.S. Senate in 1953, and the presidency, taking the oath of office in 1961. But physical pain wasn’t the only challenge he would overcome.

In 1953, Kennedy married Jacqueline Bouvier. The couple quickly embarked on building a family, but a series of tragedies made it questionable they would be successful. Jackie’s first pregnancy ended in a miscarriage in 1955. A second pregnancy resulted in a still birth in 1956. But they finally realized their dream of a family in 1957 with the birth of a daughter, Caroline. Their son, John Jr., followed just 17 days after his father won the 1960 presidential election. A second son, Patrick, arrived in August of 1963 but tragedy wasn’t done with the Kennedys. Patrick died just two days later.

An assassin’s bullet would fell the young president just three months later, closing the chapter on Camelot once and for all.

Along the way and in spite of much adversity, Kennedy’s career is marked with achievements–any one of which would have cemented his place in history. His best-selling book at the age of 23 changed public sentiment in favor of the war. His service in the Navy made him a household name. While in the Congress, Kennedy’s support proved influential in dozens of legislative efforts including matters of labor relations, public housing, and establishing the Cape Cod National Seashore. As president, he established the Peace Corps, navigated the Cuban Missile Crisis, and laid the foundation for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Though Kennedy’s time in public service was far from spotless (see: the Vietnam Conflict, numerous affairs, and a deep and abiding tendency toward nepotism), he’s remembered as a progressive, young, inspirational leader whose short presidency shepherded the nation through some of its most tumultuous times.