Acquisitions I: Souvenirs from a life with art

My first encounter with art happened on a staircase landing.

Sometime in the late Spring of 2002, I an invitation to a gallery opening from Carol Parsons. I had done an article on her home, Layton’s Castle, and during the attached photo shoot, we shared cocktails in her library. We spent the better part of an afternoon discussing her life and ideas on politics, literature, architecture, and archaeology.

She invited me on a walk through the gallery of her home, a wide hallway that bisected the sprawling red brick castle, and she pointed out this painting and that artist. I had long been interested in art, but this was my first interaction with art in any meaningful way. Beyond a visit or two to local art museums, I was wholly unexposed to painters and painting, which was shocking, especially considering I knew several artists and counted them among my dearest friends.

A few days after our visit in her home, Carol left a message for me with the magazine office. I returned the call only to be greeted with the same, polite southern drawl, “Michael, it’s Carol Parsons. I want to invite you for drinky drinks at the Castle and then we can go to a friend’s art gallery. He has a show opening tonight.”

Having never been to an art gallery, I wasn’t sure what to expect. But at the appointed hour, I arrived on the landing outside the second-floor entrance to the castle and Carol greeted me with a gin and tonic, my drink of choice at the time. She had made a point to remember. We visited briefly and then departed for the gallery of Edmund Williamson.

As I made my way around to each of the pieces — Edmund’s works were of bayou scenes and cypress trees, I discovered a painting, orphaned on the staircase landing. This painting was by the other artist featured in the show, Randy Leggett.

As I made my way around to each of the pieces — Edmund’s works were of bayou scenes and cypress trees, I discovered a painting, orphaned on the staircase landing. This painting was by the other artist featured in the show, Randy Leggett.

Compositionally, there’s a lot going on in this painting. A work of contemporary expressionism, the primary viewing space is a foundation of aureole, framed by a red and black border which lends the effect of a floating book, turned on its side. There are windows across the top, and near the center, a series of staircases lead to a heavy door, from which is hinged what appears to be a sliver of scroll.

Around the left and right margins runs an inscription, in German:

We have no place to go, for everywhere there are shadows.

When I see it, I think of the Holocaust and the souls lost. After multiple attempts to reach the artist, it’s “truest” meaning is still locked away.

To say this is a haunting work is an understatement. Even in 2003, standing in that gallery, I couldn’t bear to look away from it and returned to it, again and again throughout the evening. Sometime before the bar closed but after the last of the canapés had been consumed, Edmond approached the painting and placed a red sticker on the corner. I sighed.

“Someone bought it?”

Edmond nodded. “Yes. You just did.”

I protested. I was a waiter with very little expendable income. I couldn’t afford a painting like that.

“Don’t worry, Michael. For you, it’s half-price.”

I had only just met Edmond a few months before. Why should he provide me with such largesse, such deference? I couldn’t accept, I insisted. He would hear nothing of it. I could pay him out, he said, at $10 a month until it was paid off, if that’s what it took. When at last I asked him why, he said it was simple.

“You’ve been coming back to this piece all night. When a piece of art speaks to you like this one does, find a way to buy it. You’ll always have it, and it will always speak to you,” he said. “Come pick it up tomorrow.”

Over the last two decades, the painting — which we refer to as “the Leggett” in our house — has hung in an imperial red and walnut paneled lakeside dining room, on a utility room door I had covered with a piece of red fabric, over the fireplace of the second apartment I shared with my daughter. Today, it’s in our bedroom, over the blue sofa, the first piece of “real” furniture I purchased after selling off everything and moving to Nashville.

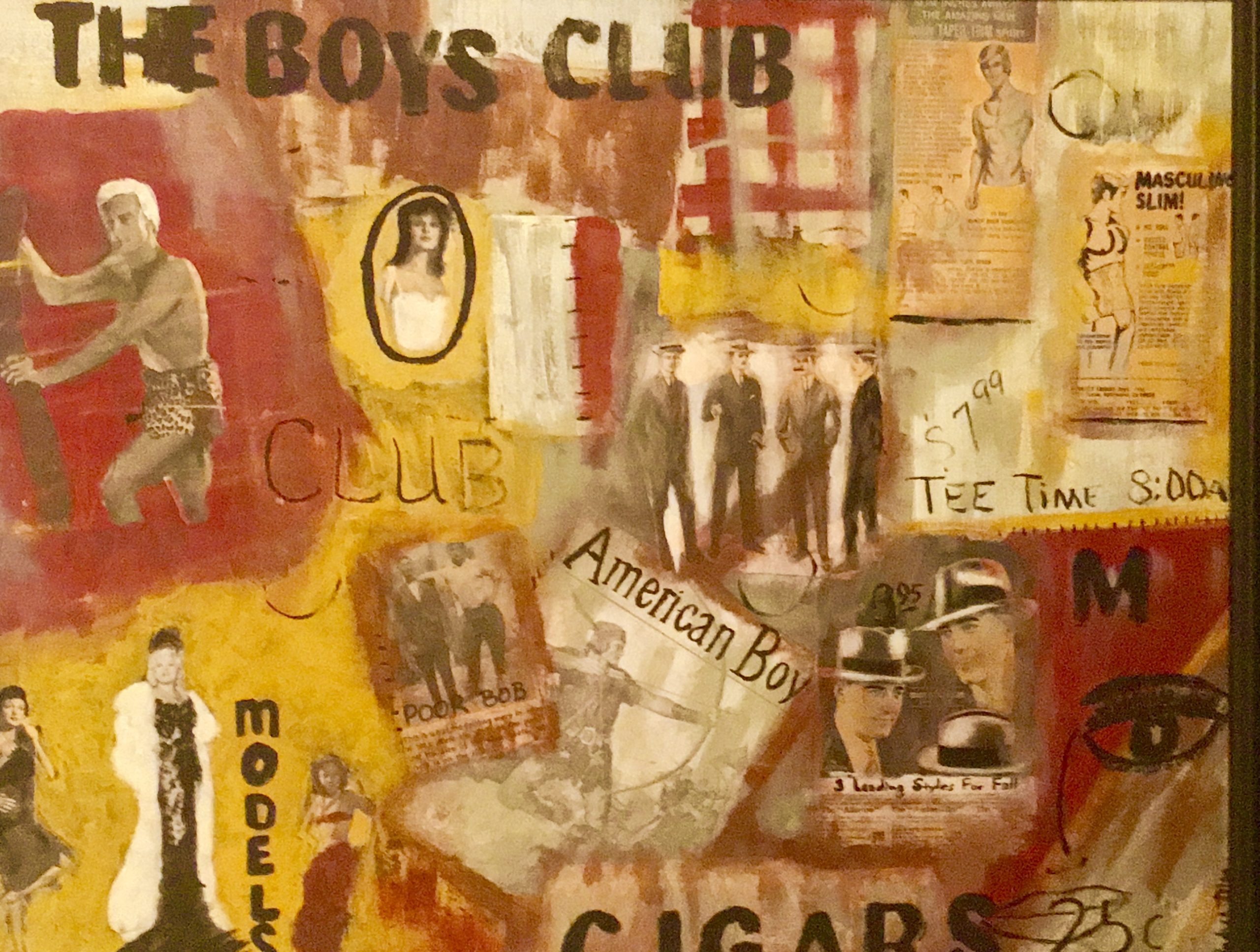

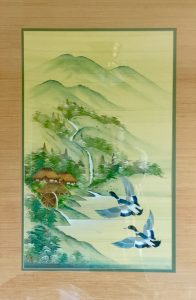

Along the way, I’ve picked up pieces from artists I know, like Jason Byron Nelson and Rob Prior, and artists I don’t, like P.J. Bellini and Kazuko Chiyo Sasaki. My eclectic taste includes architecture renderings from Pam Heidt and “the Artist of Detroit,” Bill Moss. Each piece, carefully chosen from estate sales, garage sales, Goodwills, and auction house leftovers speaks to me in some way similar to the Leggett. When last year a dear friend decided to KonaMari her life, my collection nearly doubled in size, with new works that include a cubist dining table by Kenn Kotara, abstract expression from David Lowe, and contemporary impressionism of Louisiana bayous compliments of Rhea Gary.

Along the way, I’ve picked up pieces from artists I know, like Jason Byron Nelson and Rob Prior, and artists I don’t, like P.J. Bellini and Kazuko Chiyo Sasaki. My eclectic taste includes architecture renderings from Pam Heidt and “the Artist of Detroit,” Bill Moss. Each piece, carefully chosen from estate sales, garage sales, Goodwills, and auction house leftovers speaks to me in some way similar to the Leggett. When last year a dear friend decided to KonaMari her life, my collection nearly doubled in size, with new works that include a cubist dining table by Kenn Kotara, abstract expression from David Lowe, and contemporary impressionism of Louisiana bayous compliments of Rhea Gary.

So substantial is the volume of art on our walls that my wife, Alyssa, shudders when she knows I’m on my morning Goodwill run or attending an estate sale. I hesitate to point out that she has mastered the “art tour” whenever we have company over for the first time. When my daughter moved into her first apartment, I offered her almost carte blanche choice on the art. She could take anything, I told her, with the exception of the Picasso. Her response was, to say the least, terse.

“I want bare walls for a while. I’m tired of living in a museum,” she said. She’s since begun hanging art of her own findings — and a, choice few pieces I’ve sourced for her in the last year.

One thing curiously absent from our walls: posters. We own no posters, hang no prints. We’ve curated a collection of things that speak to us, and along the way we’ve supported the artists who enrich our lives. Whenever I hear someone has moved into their first apartment, I suggest they follow skip the posters in favor of supporting artists. Skip the movie posters in favor of original works. Make friends with artists. Frequent the starving artist show at the community college. Watch thrift shops. But, no matter where you get your art, apply Edmund’s edict: Hang art that speaks to you.