The Case for 2020: Year In Review

Alyssa and I were nestled tightly together on the sofa, watching Bridgerton and waiting patiently. At 11:50 p.m., I removed a bottle of Korbel from the refrigerator and popped the cork. At 11:55, I poured two glasses and sat them on the table. All the while, Miss Bridgerton and the Duke danced in the background. When Alyssa reached for her glass at 11:57, just three minutes shy of midnight, I shooed her hand away.

“Not yet. No bad luck.”

That I was even awake this late was, itself, a testament to my commitment and drive. A chronic early riser since childhood, I am rarely awake past 11 p.m. when I’m home. But this year would be different.

I would see the end of 2020 come hell or high water.

And I wasn’t alone, as the presence of a bottle of Korbel demonstrated. Every year, I find a bottle of real, French champagne for New Year’s Eve. It’s one of my traditions. We celebrate en vérité or not at all. But for 2020? The only champagnes available were $80 or more, and I wasn’t about to celebrate 2020 with a bottle of Veuve or Dom. If I couldn’t find a $30 bottle of champagne, then this fucker would die, and it would die with the headache that comes with the cheap shit.

As the empty shelves in three liquor stores attested, a lot of people feel the same way. They were ready for 2020 to be over. And who could blame them? It’s been a year of hell that would make Janeway crash Voyager. Why can Elon Musk launch a car to Mars but not invent a temporal reset switch? Wouldn’t resetting the timeline and getting a “re-do” on 2020 contribute more to humanity than a free, cube-sat Internet system?

Then again, where would I be and what would my life be like had I not lived 2020?

Therein lies the challenge with this particular year, and it’s one for which I’m grateful I have a peculiar form of synesthesia. As I’ve circled around the events of 2020, I cannot help but see it as two years — one of tremendous failures, missed chances, and lost opportunities; and one of phenomenal successes, new opportunities, and brighter horizons. Dickens himself couldn’t do justice to the year in a single paragraph.

In January, before Covid struck, Alyssa and I had our entire wedding mapped out. We were going to get married on at a friend’s home — a 250-year-old castle — in Louisiana and follow a day-long wedding with a rocking party that night. We were going to take a honeymoon cruise sometime in the Fall or over the Winter. But by March, it was apparent we weren’t doing any of those things. Instead, we planned a smaller, more intimate wedding at home in Tennessee, on the acre-sized green space adjacent to our condominium. (And even those plans would change because of Covid-19.)

By mid-March, I had canceled more than a dozen work trips to conventions, to meetings in L.A., New York. At least a quarter of my income vanished. The Year of Covid would mean leaner times in the DeVault household. But with nine months to go, 2020 was far from finished with us.

In April, my daughter began having coughing fits. A grocery worker, she was deemed an “essential worker,” and she was therefore at a higher risk of exposure and infection than those of us who spent a significant portion of April and May sequestered away in our homes. For a couple of days, she hoped the cough would resolve on its own. But when she awoke one morning in a coughing fit, she found specks of blood and immediately went to the emergency room. By then, hospitals were under lockdown protocols, and no one was allowed in the room with her. They did a Covid test — negative — and a lung scan. She called me crying and scared. There were abnormalities in her lungs, and the doctors had ordered a transfer to another hospital for more tests.

In the darkest moment of her life, I couldn’t be there. I couldn’t hold her hand or kiss the top of her head. I couldn’t make bad Dad jokes or be in the ambulance with her. I wasn’t there when she awoke from the biopsy. And I wasn’t there when the doctor told her she had Stage III lymphoma.

At the same time she was facing this demon alone, my fiancée and I were undertaking a medical journey of our own. A family member had been diagnosed with breast cancer, and upon exploration, they discovered the BRCA gene runs in her family. Alyssa was tested for the BRCA gene and that test came back positive. While my daughter fought her cancer battle, we were spending our time with oncologists and surgeons, discussing options. The battle plan was simple enough: monitor with vigilance against breast and ovarian cancer, and at the first sign of trouble, out the offending organs will come. However, the doctors were clear: by thirty, Alyssa could expect a mastectomy and a hysterectomy no later than 40. We were comfortable enough with these outcomes until we received a letter from the doctors. Based on family history, hormone panels, and the genes, Alyssa would undergo bi-annual mammograms with contrast from now until age 25, at which point she should anticipate undergoing a bilateral mastectomy.

Nothing underscores the seriousness with which the doctors took her cancer potential more than what happened when we called the surgeon’s office to schedule an appointment to ask followup questions. The nurse answered the appointment call, and no sooner than saying Alyssa’s name were we on the phone with the doctor, who had been expecting our call. His advice: do the mastectomy and reconstruction now. Don’t wait.

Add a bilateral mastectomy and reconstruction to the medical challenges of my daughter’s cancer fight.

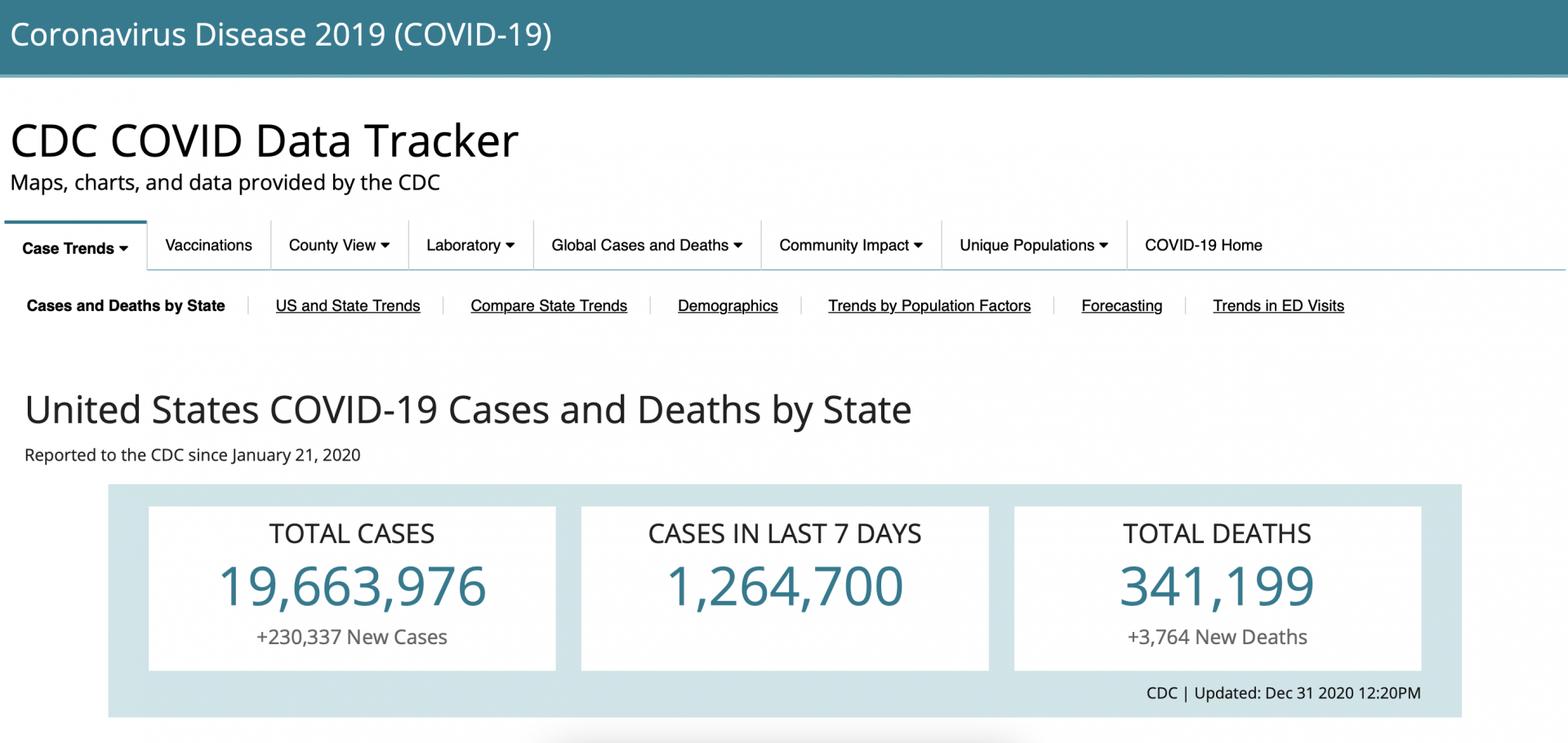

Early in November, after Alyssa’s second surgery, we contracted Covid-19 and developed pneumonia. In addition to the impacts to my health, we lost a month of work, a month of income. I almost had to go into the hospital, a prospect that terrified me almost as much as the thought of Alyssa going into the hospital. I spent the better part of three weeks quarantined in our apartment, terrified that the last time I saw my wife would be either from a gurney or on one, en route to the hospital.

Early in November, after Alyssa’s second surgery, we contracted Covid-19 and developed pneumonia. In addition to the impacts to my health, we lost a month of work, a month of income. I almost had to go into the hospital, a prospect that terrified me almost as much as the thought of Alyssa going into the hospital. I spent the better part of three weeks quarantined in our apartment, terrified that the last time I saw my wife would be either from a gurney or on one, en route to the hospital.

The horror stories we had all heard resonated with me, and my deep fear of abandonment made sure that this would be the nightmare that woke me at night.

Because of Covid-19, we canceled family Thanksgiving — a day I looked forward to every year with profound anticipation. It is, after all, my favorite holiday, as I have fond memories of celebrating it with my grandmother. Thanksgiving would be just one more casualty of the year that had, itself, become a mass casualty event.

But what of that other 2020, the alternative timeline?

I mean, we did beat Covid in our household. And that wasn’t the only “good” thing to happen this year.

When it became apparent that we would have to cancel the grand wedding in Louisiana, we planned a much smaller, more intimate affair. And miracle of miracles, Tennessee entered Phase 3 briefly in mid-June, affording us the chance to hold a wedding lakeside. We were married June 11 in front of a small, and socially distanced, gathering of friends. Our wedding also confirmed for us something else: social distancing works.

When it became apparent that we would have to cancel the grand wedding in Louisiana, we planned a much smaller, more intimate affair. And miracle of miracles, Tennessee entered Phase 3 briefly in mid-June, affording us the chance to hold a wedding lakeside. We were married June 11 in front of a small, and socially distanced, gathering of friends. Our wedding also confirmed for us something else: social distancing works.

Two days after the wedding, after the reception, after dinners at the house and a post-wedding brunch at Restoration Hardware, and more than a few thrift store trips, we discovered our officiant had been exposed and was Covid-positive the entire time. No one caught Covid at the wedding, the reception, the dinners, or the hotel. (Masks work, people. And was your hands. You nasty!)

With the first CAT scan after just two treatments, the five-inch mass in my daughter’s chest was less than 2 inches. The smaller masses on her pancreas were all but gone. Her oncologist could not contain his excitement at the results. “They’re incredibly positive. Your response to treatment is phenomenal.”

Two months later, she rang the bell. Three weeks after that, we received the results of her first post-treatment scans, and the doctor said two words that, even now, make me tear up: cancer free.

Alyssa’s mastectomy and reconstruction went well, too. The plastic surgeon delivered, and in a year or two, it will be nearly impossible to tell she’s had reconstruction at all. Better still, she has reduced her overall cancer risk by more than 60%. That’s great news for someone who was told she had an 80% chance of getting cancer in the first place.

And what about those lost opportunities, the missed trips? Professionally, 2020 has turned into a banner year.

In April, I signed a book contract to co-write a series of fictionalized memoirs. The first should be released in March. In June, just after the wedding, I began writing a screenplay that’s being shopped now for production. In December, I signed a contract to adapt a series of novels into movies.

And that raises the question: what kind of year has it been?

When I look back on 2020, will I remember it as the year we lost jobs, canceled weddings, missed trips? The year my daughter got cancer or my wife had a mastectomy?

Or will 2020 instead be the year my daughter beat cancer and my wife prevented it, the year I sold my first movie, and the year I wrote two books?

Either way, when the clock struck midnight, closing the door on 2020, my wife and I stepped out onto the balcony. As Bing Crosby serenaded us with “Auld Lang Syne,” in every direction, for as far as we could see, fireworks exploded over the trees. We may not know what we’re leaving behind quite yet, but we were hardly the only ones ready to bid it farewell.

Here’s to 2021, and here’s to hoping for a brighter horizon.